John Wyndham Covers Part 2

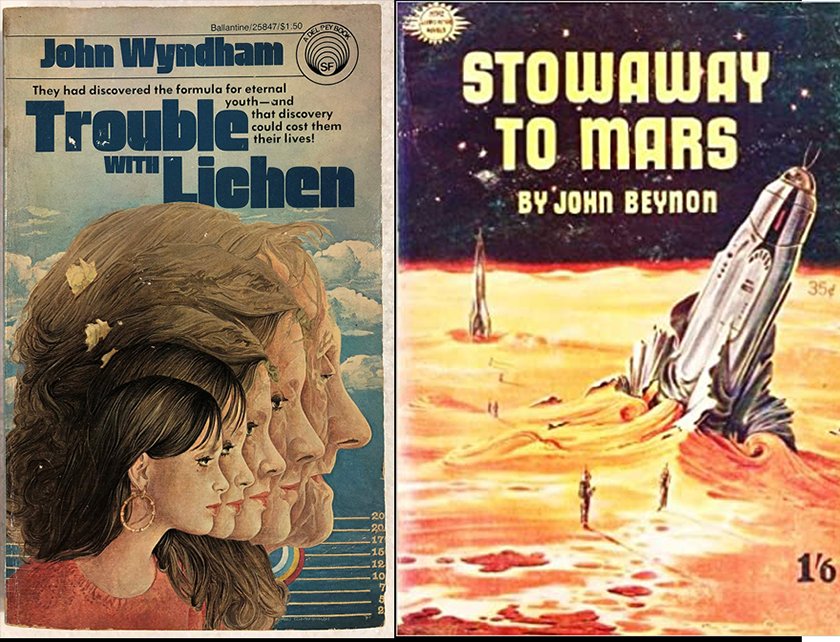

Two earlier versions of the present volumes by other artists. I Especially love the abstraction of that Penguin edition of Lichen.

The fourth and fifth books I did for Modern Library in the John Wyndham collection were Stowaway to Mars and Trouble With Lichen. One of the interesting parts of doing covers for a series of ten books by a single author is that I’m getting a kind of crash course in one writer’s work. I have done a number of book covers in the past, and something I have discovered is that if I don’t read the book in something close to its entirety, the cover will not turn out so well (this has also occasionally been true of books I disliked). I did a number of covers for novels by Richard Brautigan for a Spanish publisher some years back, and didn’t read a few of them. And let’s just say there’s a reason they aren’t featured anywhere on this website. So I’ve been doggedly reading each of these Wyndham books, even the ones that aren’t actually his best work. And it’s been kind of fascinating.

I don’t actually read much fiction, normally. I have a problem where if I start a book and I like it, it just makes me want to stop reading and go work on my own stuff. And if I don’t like it, well, life is too short to waste time on bad books. I also am a bit suspect of the whole idea of fiction. Like, why should I care about some random person’s poetic invention about how the world might be. I’m much more curious to know how the world actually is. The cliche that ‘truth is stranger than fiction’ feels very relevant to me as a reader of non-fiction. Truth is stranger, sure, but it’s also more pertinent and deeper and will, at its best expand your understanding of the world. Of course I also can see quite clearly the irony that I am, myself, a writer of fiction, for the most part. So yes, I contain contradictions. It’s also inarguable that non-fiction will always be colored by its author’s biases and blind-spots. So my prejudice against fiction is not altogether a rational stance. But there it is.

So it’s been an education to spend so much time with a single author, reading works covering his whole career, and sticking with them even when they aren’t his best. And, spoiler alert, these two books are probably not his best. But they are still kind of fascinating in their way.

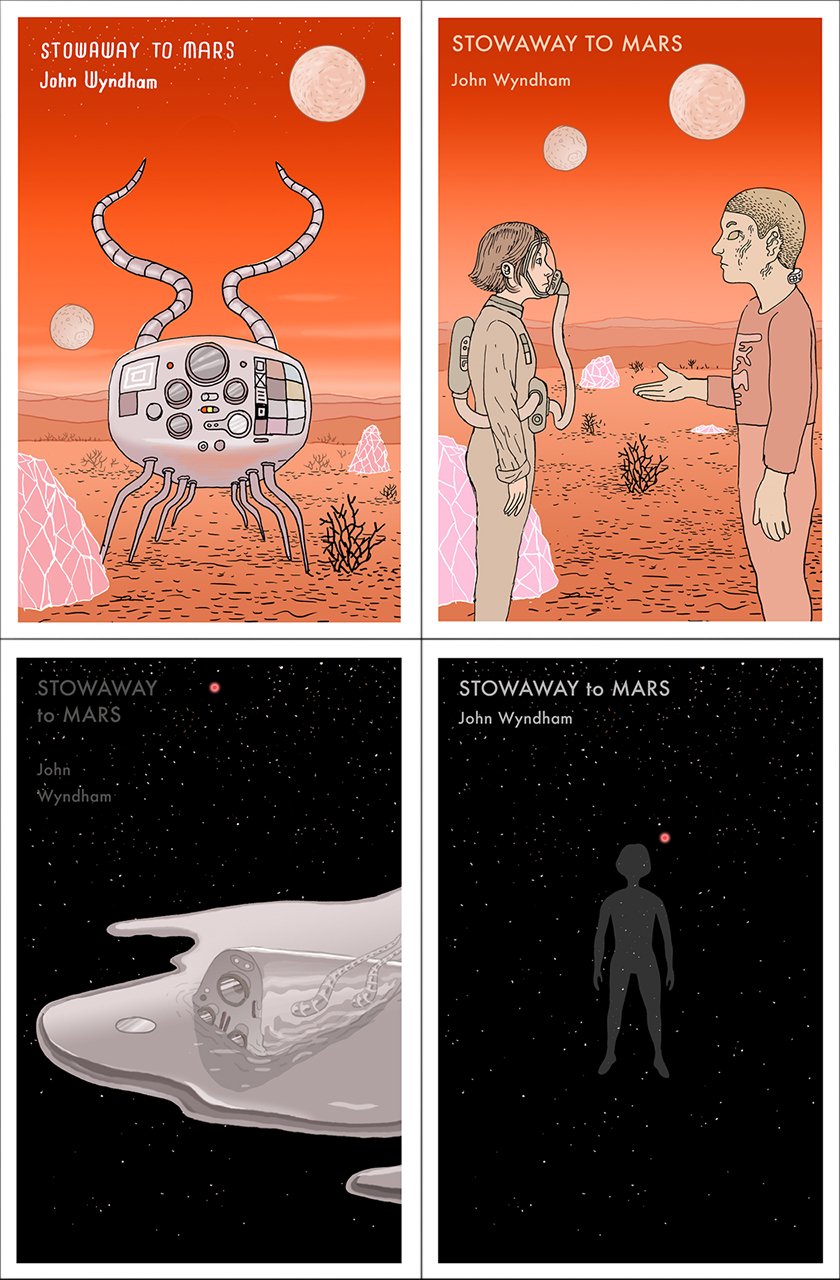

As a book Stowaway stood out to me from the others as very clearly – and unfortunately – the work of a young author still trying to find his feet. It was written in the mid-1930’s (he was born in 1903) and feels like pretty mediocre pulp sci-fi, as if Wyndham didn’t really seem to have much idea where he was going. It does end up being productive, though, as an exercise in generating ideas, several of which he will recycle to better effect later on in his career, but on its own it’s not his best work. The story starts as one thing, then tries to be at least two or three other things before it ends as something else again. In fact, by the end when I had finally gotten truly interested in the main character’s situation – which seemed clearly to anticipate a compelling sequel I might have been truly interested in – the book just kind of stopped.

Nevertheless it did have a number of good images for me to work with, including the very peculiar martian robots (see first example). These are the four sketches I originally sent in, below – one more than what I usually send for a first round. And I didn’t even include the one that ended up getting picked until a week or two later, when there seemed to be some hesitation from the other end, and more changes were getting requested than was usual. It’s also the first of the series that I designed my own letterforms for (see first sketch and final, above).

The book fits nicely into the Wyndham-as-visionary narrative in that its early chapters anticipate the idea of the Xprise – a large cash prize is offered to the first person to manage to get to another planet and back, as a spur to technological progress. It goes on to do some philosophizing about humans’ relationship to technology and there is a slightly Tolkeinesque advanced-race-at-twilight narrative, with Martians in the place of Middle Earth’s elves (this part also reminded me maybe even more so of C.S. Lewis’s dying race of magicians living among their ruins on the extra-dimensional Charn, from The Magician’s Nephew. The decline of empire in the early mid-20th-century was apparently felt keenly by English fantasists of the time). There is also an interesting, but slightly quaint and… just plain wrong treatment of what the cultural and personal impact of space travel might be and how the technology might play out. The astronauts find Mars boring, for the most part, which is strange to imagine as a throwaway plot point in 2022. So overall it doesn’t really work, but it’s kind of fascinating to watch someone speculate from the 1930’s – before either computers or space travel or mass media were really a thing – about phenomena we now look back on from even further into the future and have fully assimilated.

We also get to watch Wyndham try out ideas that then pop up again in subsequent works, sometimes only slightly modified. Every author is probably subject to this tendency, and I’m certainly aware of it in my own work. Some ideas, whether visual or narrative or characterological or linguistic, just don’t want to let you go. The best case scenario is to try and be aware of your tics and tendencies and to try to use them in interesting ways – to expand on them, extrapolate them, push them in new directions. Worst case is you just spend your life repeating yourself. On a broad level Wyndham is clearly beginning to play with his proto-feminist impulses in the book which becomes a theme in much of his subsequent work. More specifically, Stowaway is the first of at least two books to begin as a sort of noir-ish who-dunnit before becoming more solidly sci-fi. Wyndham’s earliest work was detective fiction, and so maybe it was a genre he was loathe to leave behind entirely. Or perhaps he imagined himself as daringly erasing the borders of genre itself by combining the two. It’s also the first book in which some item of advanced/alien technology spontaneously melts itself to avoid capture. In both of these cases the recapitulation happens in Plan for Chaos from 1947, which wasn’t published until after Wyndham’s death, and which I’ll hopefully get around to discussing later – I just sent off sketches for it a couple of days ago. Stowaway also anticipates a human/alien pregnancy situation that ends up as the whole basis of The Midwich Cuckoos, one of his two most well known (and best) books.

Stowaway to Mars makes a slightly odd pairing when read together with Trouble With Lichens. The latter book came much later, being published in 1960 and is clearly the product of a more developed artist. In a way the twenty-three years that separates the two books doesn’t seem like all that long in the course of a whole career and a life – he still had two more books in him after this – but given that the interval contained an entire Second World War, the advent of the nuclear age, the end of the Great Depression, the spread of mass media and youth culture, the further decline of the British empire and the beginnings of actual space-flight… it was a massively consequential two decades.

The final design for Trouble with Lichen.

Trouble with Lichen is about two scientists who discover a rare example of the mossy species that can retard the process of aging, and the cultural and political fallout that follows the discovery. It’s one of his more overtly feminist-tinged books. One of the scientists is a woman who starts a line of beauty products secretly using the technology, more or less as a way of both utilizing, and promoting the unacknowledged power of her sex. She’s cast as a sort of undercover gender revolutionary in a weird, very 1950’s kind of way. Again, like in Stowaway Wyndham’s imaginings of the future in Trouble with Lichens feel a little off. And his understanding of feminism is a little odd as well, looking back from 2022. So again he’s at once a keen observer, and also basically wrong. But in interesting ways. The book again weaves an almost classic whodunnit into its speculative fiction frame – its first chapter is set at the main character’s funeral following her apparently violent, mysterious death. The rest of the book picks up by chronicling her origins and the events that led to that point.

Below are some sketches. The first of these was a revision the art director asked for with the bloody bullet holes I’d originally included, removed. I actually designed type for the final for this cover as well (see the fourth image), but it didn’t end up getting used.

On its own terms, despite being a more coherent story, the book fell a little short for me. In several of his works Wyndham has a habit of having characters talk about things that are happening in the world, rather than depict the actual events. He’s got a little bit of a ‘show don’t tell’ problem as your freshman creative writing instructor might say. And Trouble With Lichens is maybe the most egregious example. Large swaths of the book is just people having conversations about events they’ve seen or participated in or heard about, but only rarely do we get to watch the action directly. He’ll just sit two characters down in a restaurant and start them talking for, like, ten pages, so you get everything second or third hand. It starts to feel a little tedious at times, like there’s a veil between you and the actual events. Which is too bad, because some of the drama, along with his speculations is genuinely interesting and original.

• • • • • • •

After these I did Web, the other book that never saw the light in Wyndham’s lifetime. Outward Urge and the aforementioned, technology-melting Plan for Chaos are still in progress, and there will be two more after that. So stay tuned.

Two more earlier versions of Trouble with Lichens and Stowaway to Mars.